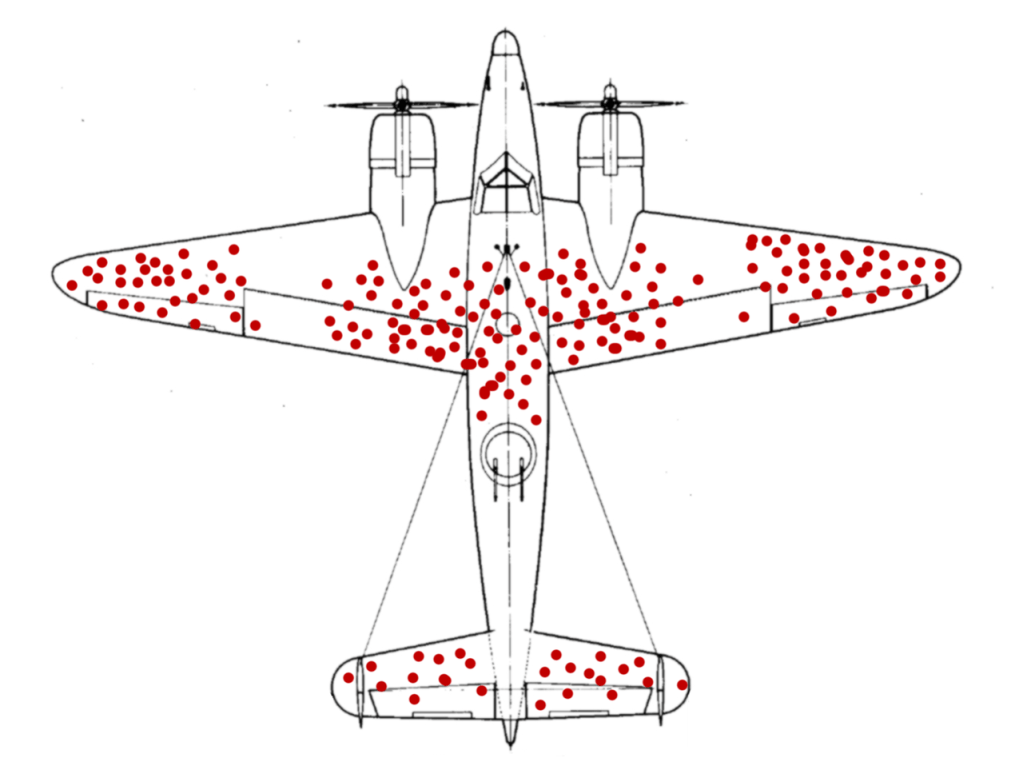

I recently came across a story about a mathematician named Abraham Wald who served for the allies in the 2nd world war. Abraham had been tasked with figuring out the best placement and ratio of armor on America’s Bombers. Adding armor to planes made them slower, less efficient and less maneuverable. The heavier they were, the less bombs they could carry and the shorter the distances they could fly. A number of bombers returning from duty were analyzed to see where they were taking on the worst damage and it was assumed these were the areas that needing the most armor. Many of the returning planes were sustaining heavy damage everywhere but the engines.

Abraham’s suggestion opposite to most. He proposed that the engines were the areas needing the most protection because only the planes that did not sustain heavy engine damage made it back. Those with engine damage did not. This mathematical bias problem has since been termed as “survivorship bias”.

Wikipedia defines survivorship bias as: “the logical error of concentrating on the people or things that made it past some selection process and overlooking those that did not, typically because of their lack of visibility.” More simply put, we tend to focus on survivors and winners, ignoring all those who failed.

While not directly related, it made me think of the term that “correlation does not equal causation” and one particular field scale trial we recently ran looking at the benefits of polymer coated urea (PCU) in wheat.

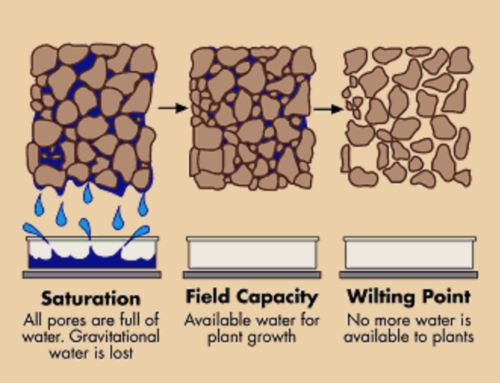

The trial was set up where we replaced a percentage of our midrow banded Nh3 with seed placed polymer coated urea so our total nitrogen applied was the same. In our heavy clay soils, nitrogen is often prone to early season losses due to excessive moisture causing denitrification. We were wanting to see if the slow-release N would give us a yield or protein response by keeping nitrogen available for later use.

The result if looking strictly at yield was a statistically significant 6% yield increase in favor of PCU. But when we looked into the data further, while we saw a difference in yield, we did not see any difference in protein levels. What was really interesting is we observed a significant difference in plant stands. The seed placed PCU had resulted in a reduced plant stand count even though we were well within what would be considered safe limits that would not normally cause seed burn. PCU should give us an increased level of seed safety due to its slow release properties.

So did the PCU give higher yields despite a reduced plant stand? If you remember I mentioned that there was no significant difference in protein. What I didn’t mention was that the wheat yields where in the mid 50’s despite fertilizing for a 70+ bushel crop. Growing conditions were dry that season therefore we don’t believe denitrification was a problem. Nitrogen should not have been a limiting factor in either treatment (this is reinforced by the lack of difference in protein levels).

So why did we see a yield increase with the use of PCU? It looks more like a reduced plant stand may have made better use of available (limited) water resulting in higher yields.

So in conclusion I want to make the point that things aren’t always what they seem. In agronomy as in engineering there are many causes and effects. Only with experience can you learn to look through the noise, trying to rule out as many variables as possible.